16,000 Miles With the Sea Gull: Schooner Days XXXVIII (38)

- Publication

- Toronto Telegram (Toronto, ON), 12 Mar 1932

- Full Text

- 16,000 Miles With the Sea Gull

Schooner Days XXXVIII (38)

So much surprise has been excited by the statement in last Saturday’s Telegram that the father of the late Capt. Frank Jackman, recently deceased, took an Oakville schooner from Toronto to South Africa and back, that the facts of this voyage are, at some cost of repetition, here given in detail.

THE Sea Gull left the foot of Lorne street in June, 1865, with a cargo of hardware, flour, groceries, buggies, and whiskey in the hold and knock-down houses on deck, shipped by a Mr. Davids of Toronto and Reford and Company, of Toronto and Montreal, to a South African consignee named Lysle. Capt, Frank Jackman Sr., was in command; James Jackman, his nephew, was mate. Capt. May, a saltwater man, went as navigator. There were four men and two boys in the forecastle, and one cook. Ten hands all told, to take the vessel sixteen thousand miles, out and back; half-way around the world. The last of these argonauts of the Sea Gull, Hooker Evans of Port Credit, died only two years ago.

The Sea Gull drew but four feet light, with her centreboard up, and while she loaded to ten feet on Lake Ontario she only drew eight feet with her outward cargo for South Africa on account of the St. Lawrence canals; then as now the ball-and-chain on deepwater navigation for the lakes.

She went down the St. Lawrence and through the Cabot Straits and south and east across both Atlantic Oceans. Her outward passage was slow. She was a long time in the doldrums of the Equator, and the flying fish that came aboard stank horribly where they lodged between the sheeting of the knockdown houses which formed the deckload. It was September before the Sea Gull got around the Cape of Good Hope and breasting the surges of the Indian Ocean, worked up to Durban or Port Natal, on the east side of the dark continent. She came in across Port Natal bar without the aid of either pilot or tug, a feat never before attempted by a sailing vessel.

Lake Ontario pluck and a freshwater centreboard were the secret. By hauling up her board the Sea Gull reduced her total draught from seventeen feet to eight. The centreboard had its drawbacks, too. In the warm southern waters the shipworm breeds. The Sea Gull was not coppered. Her lake crew counted on getting her unloaded and scraped and scrubbed clean of worms and barnacles before serious damage could result, and they carried out their program. But in the still watches of the night, on the way home, they could hear the teeth of the shipworms working like augers in the dead water inside the slot of the centreboard box.

There was no way of scrubbing that out. They poured cinders and ashes from the cabin stove down the slot, and hove the centreboard up and down, a wearisome job. But it saved the ship. They were afraid the box would be eaten through from the inside, and that the board would be so chewed that it would break off as she rolled.

The lumber which, in addition to the houses, formed the deckload, sold for sixteen cents a foot in Durban. But the 150 kegs of Canadian whiskey proved a drug on the market. It was too mild for South African taste, then educated to “that hellish liquor,” rum. So it was put back in the hold. The shaking it got, and the seasoning in sea air, during-the thirteen months it was away, so mellowed it that a snort of Sea Gull whiskey was the highest courtesy hospitality could offer in Toronto business houses for years after the brigantine returned.

But it was some time before, these amenities were practised. The Sea Gull lay for months hunting up a return freight in Durban.

At length she secured enough pepper, ivory, sugar and molasses to make it worth while starting for Boston, and with great good luck found passengers willing to pay one hundred dollars apiece for the voyage. There were thirty-seven of these, and among them was Mr. George Hare, father of the late Mr. Charles T. Hare, who died in Montreal last year.

Mr. Hare kept a journal, which the writer has been privileged to copy. This begins:

“Being a passenger in the good Brigantine Sea Gull, on a voyage from Port Natal, S.A. to Boston, U.S., we left on the evening of the 21st Dec., 1865, and after a stormy fortnight got to within sight of Table Mountain, having been hove too, as the sailor says, twice, and scudding another day with a small corner of our topsail set before another gale, as we rolled and labored so fearfully in the tremendous sea that it was getting rather dangerous to our vessel, which was what is called a centreboard one, that is, to the uninitiated, a vessel with a moveable keel, and besides being very broad she labored, and in fact was by no means a comfortable vessel to be in in a heavy storm.”

This glowing tribute is followed up by some vigorous pen-and-wash illustrations in the notebook Mr. Hare kept. He was of seafaring stock, a son of that Lieut. Charles Hare, R. N., who commanded His Majesty's schooner Bream and His Majesty's brig Manly in the Bay of Fundy in the War of 1812. With a sailor's eye for detail, Mr. Hare pictures the Sea Gull leaping like a porpoise when hove to off the Cape of Good Hope, under the head of the mainsail, or scudding under the starboard goosewing of the close-reefed fore top sail, amid huge curling seas, that seem to take her just forward of the main, rigging. Still, his sketches always show her "on top," and she came through very much, hard weather without damage.

Three months from the Cape of Good Hope to Cape Cod is not bad going for a hundred-foot keel. The Sea Gull took a fortnight for the 755 miles between Natal and Table Mountain. This was due to the heavy gales in which she had to heave to, or scud and lose ground. She had a "balance reef" in her mainsail, running from above the double-reef earing to the throat of the sail, which gave her a snug triangle of canvas for a storm trysail, the main gaff being peaked up high between the lifts.

Scudding before the gale instead of continuing hove to was an alternative probably only possible from her shoal-draught centreboard hull. On such an occasion, of course, the board was entirely housed in its box —which would have made a grand receptacle for wave-oil.

In the fortnight after turning the Cape the Sea Gull made the 1,500-mile run to St. Helena, where she touched for water and fresh vegetables. The next 1,500 miles to the equator were slower, for her unprotected bottom was becoming foul with weeds and barnacles in the warmer water.

It was on Feb. 9th, 1866, three weeks after she left St. Helena, that she hove to off the St. Paul Rocks, 55 miles north of the line and sent her boat to shoulder its way through schools of sharks and clouds of boobies, for a close look at this desolate group. The crew tried to fish for groupers, outside the line of surf, but the sharks were so thick they had to poke them away with oars and pike poles before they could get their hooks to sink; and then the beasts snapped the bait.

Exactly a month later, on March 9th, the Sea Gull was off Bermuda in a gale of wind, under close-reefed fore topsail, double-reefed mainsail, and foretopmast staysail.

Mr. Hare’s lively picture shows her again leaping the wave backs with a great deal of weather side exposed, and her faithful "fly, " or conical windfinder of bunting, streaming from the main-truck. That little detail is convincing evidence of her Great Lakes origin. No laker ever went without such decoration.

Whether she put into Bermuda is it not known, but by March 30th she was safely in Boston, having covered some 8,000 miles of bottom in 98 days.

She had heavy weather coming on the Atlantic coast. By the time she got in with Cape Cod it was snowing and blowing, and the little brigantin was so iced up that she was unmanageable. Her centreboard was frozen in its box and her sails and gear so loaded with ice that it was impossible to furl or trim what canvas was up, or set anything in its place.

Capt. Jackman told his passengers there was little chance of their lives probably strike the beach before daylight. Mr. Hare wrote a farewell message to his family and tied it around his corpse might be identified. But he had the pleasure of delivering it in person, for by God’s mercy the Gull flew clear of the Cape and into safety in Boston Bay.

It was in Boston that Capt. Jackman left his ship while she unloaded, and came home by rail in April for a surprise visit to his family, as told last week. His young son Frank did not know him with the beard he had grown.

Returning to Boston, he loaded flour into the Sea Gull, took it to St. John’s, Newfoundland, sailed from there to Sydney, Cape Breton, and loaded coal for Montreal; one of the first cargoes of Nova Scotian coal to come inland.

From Montreal the Sea Gull came light up the canals and St. Lawrence River to Kingston. This was a great wood port at the time, and the Sea Gull loaded a prosaic cargo of cordwood for Toronto. All the steamers and locomotives as well as most homes and factories burned wood in those days. The fuel trade was enormous.

The Sea Gull arrived in Toronto in July, 1866, thirteen months after setting out. Her centreboard had furrowed sixteen thousand miles of water. She left with the echoes of the American War thundering. She came back to Toronto all in an uproar over the Fenian Raid. The battle

of Ridgway was less than a month old.

The Sea Gull was built in Oakville by John and Melancthon Simpson in 1864, for Capt. Frank Jackman, Sr., Capt. John Murray, and others, at a cost of $15,000.

Her freight on the South African voyage was $9,000 and the profits $2,000.

She was a moderate-sized vessel, for her time, 105 feet long, 22 feet beam, and 10 feet depth of hold. Every account regarding her published in the last thirty years has perpetuated a typographical error in the Landmarks of Toronto, which made her of the absurdly impossible breadth of 42 feet, The careful repetition mistake, even by the most pretentious historians, shows the common source of their information.

Her registered tonnage was 201, which meant that she had a carrying capacity of 400 tons dead weight. She was a staunchly built schooner of the prevailing lake type, rather broad, flat on the bottom, with a centre board.

She had a pretty outcurving clipper bow, with a gilt gull for figurehead, and trailboards leading back from it. She was painted pure white with green stripes.

Originally rigged as, a schooner, she was changed to a brigantine for the ocean voyage. This was accomplished, by giving her a new foremast, in three pieces, with a foreyard, topsail yard, and topgallant yard. The square sails so provided were more comfortable for running long distances with favorable winds. Her staysails were set between the masts. Before coming home, probably in Boston, Capt. Jackman added an upper topsail and a royal, and when the brigantine got back to Lake Ontario she was given a skysail to please old Capt. Taylor, who was interested in her.

The skysail was a very small strip of canvas, on a yard eighteen feet long, but it made the sixth square sail on the Sea Gull’s foremast, and gave her the distinction of being the only vessel to set a skysail on fresh water. The staysails between her spars were also increased in number to four, so that she had a very ambitious appearance.

Another change made in her while in South Africa was to shorten the head of her mainmast by eight feet.

Some time after returning to Lake Ontario the Sea Gull reverted to her original schooner rig. She was sold to Oswego and ended her days as a towbarge, being accidentally burned at East Tawas, Mich., in 1888. So well built was she of Trafalgar township white oak that when she carried away the headgates of one of the Welland Canal locks and was hurled back by the inrush of water from the lock above, the gates behind her crushed her stem in until it took the shape of the V they formed, but she did not leak a drop, and her cargo was unharmed. Her American owners of the time had to deposit $30,000 to cover the canal damage. It was, as already said, cordwood the Sea Gull brought home, instead of sandalwood and ivory, apes and peacocks from the Antipodes. Her stoutest souvenir of South Africa was a keg of the rum which put the Canadian whiskey to flight. When Capt. Jackman served a very modest sample of it as the Sea Gull lay on exhibition et the foot of Yonge street Alderman Baxter declared it curled crystal shavings off the inside of the tumbler.

Mrs. F. Webb, 1067 Logan avenue, possesses a portrait of the schooner Northwest, drawn in 1885, when that little "last survivor" was new, by the prolific Charles Gibbons, marine artist, and tug engineer. She has written to The Telegram, inquiring for the artist’s address. Sorry to say Charlie Gibbons answered his last bell and signed his last picture some time ago. Capt. Frank Jackman, Jr., his employer in the tug Frank Jackman, died last month. His son, Norman Jackman, lives at 43 lona avenue.

Captions

HITTING THE HIGH SPOTS- A sample page from tbe logbook by Mr. George Hare, a Sea Gull passenger from South Africa.

¨

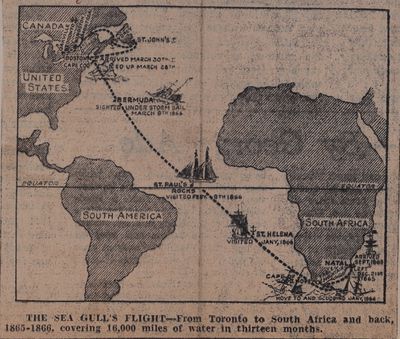

THE SEA GULL'S FLlGHT -- From Toronto to South Africa and back, 1865-1866, covering 16,000 miles of water in thirteen months.

- Creator

- Snider, C. H. J.

- Media Type

- Newspaper

- Text

- Item Type

- Clippings

- Date of Publication

- 12 Mar 1932

- Subject(s)

- Personal Name(s)

- Davids, Mr. ; Jackman, Frank Sr. ; Jackman, James ; Evans, Hooker ; Hare, George ; Simpson, John ; Simpson, Melancthon

- Corporate Name(s)

- Reford and Company

- Language of Item

- English

- Geographic Coverage

-

-

Saint Helena

Latitude: -15.95 Longitude: -5.7 -

Massachusetts, United States

Latitude: 42.35843 Longitude: -71.05977 -

KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Latitude: -29.8579 Longitude: 31.0292 -

Ontario, Canada

Latitude: 44.22976 Longitude: -76.48098 -

Quebec, Canada

Latitude: 45.50884 Longitude: -73.58781 -

KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Latitude: -29.86667 Longitude: 31.05 -

Pernambuco, Brazil

Latitude: 0.93333 Longitude: -29.36667 -

Ontario, Canada

Latitude: 43.65011 Longitude: -79.3829

-

- Donor

- Ron Beaupre

- Creative Commons licence

[more details]

[more details]- Copyright Statement

- Copyright status unknown. Responsibility for determining the copyright status and any use rests exclusively with the user.

- Contact

- Maritime History of the Great LakesEmail:walter@maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca

Website: