Catching a Ketch: Schooner Days CCLXXIII (273)

- Publication

- Toronto Telegram (Toronto, ON), 2 Jan 1937

- Full Text

- Catching a KetchSchooner Days CCLXXIII (273)

_______

SEVERAL kind readers of Schooner Days have telephoned and written about the English ketch Ceres, whose demise in her hundred and twenty-fifth year had been recorded in The Telegram. Putting it briefly, the Ceres was built on the Bristol Channel in 1811 and was wrecked in the Bristol Channel in 1936 while still in harness. She had plodded through the Napoleonic wars and run the gauntlet of French and American privateers in the English Channel, survived the introduction of steam propulsion, saw iron displaced by steel and steam by gasoline, and kept on carrying her cargoes of flour, coal, stone or whatever she could get, until Father Neptune claimed her. She was always just a wooden sailing vessel. Once she was rebuilt and lengthened. Last year auxiliary engines were installed Perhaps if she hadn’t added these frills to her 1811 petticoats shsne would have been dancing yet.

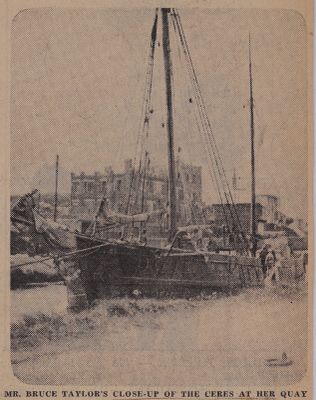

One of the readers mentioned was our yachting friend, Bruce Taylor the younger. He had had the good fortune to see the Ceres when he was in England in the summer of 1935, and to photograph her in harbor. His picture is the best of many which have been sent, and is reproduced here.

What is a ketch?

There is no catch in the question or answer. The ketch is a definite rig for a sailing vessel. It is of respectable antiquity, traceable back for about three hundred years and very popular to-day with cruising yachtsmen. Many of these prefer it to the schooner rig, for ease in handling. It may not be as efficient as the schooner rig for going to windward, but it is much more easily reefed and the position of the mast interferes less with the layout below.

Details of the ketch rig have varied greatly from time to time but they have always had this common characteristic: There are two masts and the shorter mast, is the aftermost of the two. Usually the taller mast, called the mainmast, is pretty well inboard from the bow. The shorter mast is the mizzen.

The older the vintage of the ketch rig the nearer amidships the mainmast. This appears to be connected with the fact that two hundred years ago the ketch rig was used, perhaps specifically devised, for bomb-throwing vessels, which had heavy mortars mounted on deck where the breadth was greatest forward of amidships. The mainmast was stepped just abaft this gun, and the headstays leading from it were of chain, so as not to catch fire, as tarred rope would, from the red-hot shot or bombs which the mortar fired. The shorter mast, the mizzen, was stepped well aft, but not in the very stern, because there had to be room for the crew to work the gear controlling the mizzen sail. This had to be backed and hauled from side to side so as to cant the bomb-ketch’s stern around as she lay at anchor, that the mortar might be fired ahead without shooting away her own headgear. The gun was too heavy to pivot or turn easily in its bed or carriage, so the crew had to turn the ship, to bring it to bear. For the same reason the bomb-ketch had a very long bowsprit with several jibs on it, three or four, to assist in canting her around.

This inherited feature is quite noticeable in the picture of the Ceres. This ketch rig for small coasters such as the Ceres was to be found all over the waters of Europe, from Constantinople westward, always marked by a standing bowsprit and multiple, jibs, whether the ketch was English, Spanish, French or Italian. It always distinguished the coasting ketch, used for freight, from the fishing ketch or the ketch-rigged Thames barges. These latter ketches had fewer headsails and bowsprits that could be topped up or run inboard—necessities in their calling.

I never saw the Ceres, and now I never shall, but I did see an English coasting ketch of exactly similar design, dimensions and destiny the first time I was on the Bristol Channel, in 1915. This was at Boscastle, a tiny port on the north coast of Cornwall, which the Ceres herself often patronized. Appledore, Bude, Bideford and Barnstable, her usual ports, were just around the corner.

The ketch I saw was the Francis, Beddoe, of Bristol. There was a, clatter of heavily nailed shoes on5 the cobble stones outside the slatef walls of the Napoleon Inn and half the population of Boscastle ran by shouting “Ship’s coming in! Ship's coming in!” Down the steep hill-street I pelted with them till we crossed the tiny river Jordan, where the rising water showed that the evening tide had turned and begun to flow in. There was a tremendous 1 uproar outside, as the waves of all the Atlantic pounded the ironbound cliffs and spouted in breakers a hundred feet high. The Jordan flowed out through a notch like a saw cut, with rock walls bn each side as high as Scarboro Bluffs.

This notch framed momentary glimpses of a little black vessel with mainsail and mizzen set and a range of jibs run down on her steep bowsprit. She was rolling and rearing outside the line of breakers with no wind at all in her flailing sails. She had been there since noon, I was told, kept off the coast by the ebbing tide, and unable to make any headway in the calm. Now the flood had begun, and the towboat had gone out for her.

The towboat was just visible occasionally—a twenty-foot skiff, tossing on the crest of seas as high as she was long, and disappearing completely in their hollows. She was rowed by six men, and they would get seven shillings if they did their job. This was to pull through the surf, get a line from the ketch, and tow her in, by main strength, and the help of the tide, for a distance of half a mile altogether, some of it through seas like housetops and the rest up the ruffled river into which they poured, and so on to the little quay.

They did it. There was nothing dramatic about it. Their skiff stayed right side up for a wonder, their oars dug the mountain waves, the Francis Beddoe swayed and rolled astern of them like a tiny elephant towed by an ant. When she got in as far as the quay her scuppers were still streaming with the water that had splashed in over her heavily-built bulwarks, and her stowed sails were sodden with a salt soaking; but the little skiff that had dragged her in had no water above her floor boards. Marvellous boatmen, these men of the Cornish coast.

The Francis Beddoe was just such a ketch as the Ceres. The English coasts were then thick with these little vessels, and small schooners of two or three masts, most of them with square topsails. They are gone now. Two years ago, when I was sailing in one of the hundreds of the red-sailed sprit-rigged barges, that now retain the coasting trade, I was told that there were only three round-bottoms remaining on all the coasts of England. Round-bottom is the sailor-man’s name for deep-draught keel vessels, like the Francis Beddoe or the Ceres; just as sailorman is London dock slang for the bargees. They are the only sailing men left in the coasting trade. Their barges are good sailing craft, capable of making voyages from England to South America; but they are all flat-bottomed. The Ceres was one of the three round-bottoms they mentioned. And now she’s gone.

The Francis Beddoe had the same slab sides and round bilges as the Ceres, the same little crook to her stemhead, the same heavy bulwarks and thick waling around her, the same sort of stern, the same little doghouse with the rounded top on her quarter, the same rig exactly.

English coasters run closer to type; it takes an expert to tell one Thames barge from another, once her class is determined. There are “staysail barges,” “mules,” “swimmies,” “stumpies,” “sea-barges,” and so on, and it is not difficult to distinguish the class to which a barge belongs. But once you have got that far you have to look sharp at the paint and the name to pick your craft out, for hulls and rigs have been standardized.

Much more so than on the lakes here. Even our old canallers, modeled on the shape of a canal lock, retained plenty of individuality in their rig and finish. We had many “sister ships” but few true twins.

One would have thought that the easily worked ketch rig would have appealed to lake mariners, particularly for small craft, but it did not. La Salle’s Griffon, first vessel to breast the western waves, had the ketch rig of her time, 1679, but I have never seen a ketch-rigged commercial vessel on the lakes, although I have often seen them on the St. Lawrence, and know many ketch-rigged yachts. Our nearest approach to commercial ketches was the Grand Haven rigged schooners. The first of these were three-masters which had lost their mainmasts, and later ones were rigged on the same pattern, with a great deal of space between the mizzen and foremast, so much that they carried a mizzen staysail on a standing stay, setting up on the foresheet post. This was, of course, rather different from the true ketch rig, like that of the Ceres, with the masts close together and the mainmast well inboard.

CaptionsMR. BRUCE TAYLOR’S CLOSE-UP OF THE CERES AT HER QUAY

BUILT, WRECKED 1936 - The ancien ketch CERES,

Photographed in England by Mr. Bruce Taylor of Toronto, 1935.

HAPPY NEW YEAR TO ALL SAILORS FROM THE GULLS.

- Creator

- Snider, C. H. J.

- Media Type

- Newspaper

- Text

- Item Type

- Clippings

- Date of Publication

- 2 Jan 1937

- Subject(s)

- Language of Item

- English

- Geographic Coverage

-

-

England, United Kingdom

Latitude: 50.82435 Longitude: -4.5413

-

- Donor

- Richard Palmer

- Creative Commons licence

[more details]

[more details]- Copyright Statement

- Copyright status unknown. Responsibility for determining the copyright status and any use rests exclusively with the user.

- Contact

- Maritime History of the Great LakesEmail:walter@maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca

Website: