Cisco Fishing Out of Bronte: Schooner Days DCCCXXXI (831)

- Publication

- Toronto Telegram (Toronto, ON), 24 Jan 1948

- Full Text

- Cisco Fishing Out of BronteSchooner Days DCCCXXXI (831)

by C. H. J. Snider

IT was Schooner Days' good luck, many years ago, to step into the cockpit of what seemed the smallest of the sixteen fishboats of Bronte, a little craft named the Bug, not much over twenty feet in length.

A fisherman they called "Doc" who, on consideration must have been Walter Thomas, was putting out with a helper,—one of the Macdonalds. Acey? Archie?—no, he was lost in the Niagara later—Bill? Dalton? Johnny? or Nick?—to make a "set."

Two square trays, narrow at the bottom and wide at the top, contained the gang of nets, some hundreds of yards, which he was to spread. It looked to be a tangled mass of thread in which cedar bobs and lead sinkers had been lost without hope of recovery, but everything was flaked down as smoothly running as a yacht's halliards. The net, a cedar buoy, bored at one end to take the staff of a wheft or flag and at the other for its mooring line, some empty trays, and some beach stone ballast on either side of the centreboard box, covered the floorboards at the bottom of the Bug. She had a little deck at each end and a narrow strip of it inside her gunwales. Otherwise, wide open.

OUT TO THE NETS

No time was lost in getting under weigh. The boat had three sails; a gaff foresail and mainsail, of about equal area, but the foresail the loftier, and a jib, loosefooted and set flying, an extra sail, the first to be taken in. This jib was on a bowsprit, eight feet outboard, for the foremost was in the very eyes of her. Other boats were so rigged, some with bowsprits ten to twelve feet long.

It was natural that the jib should be regarded with distrust, for its position so far out over the water made it most difficult to handle in blowy weather and a choppy sea. This would really require a downhaul, outhaul and brail on the sail, and footropes, manropes and gaskets on the bowsprit. But the bowsprit in most of the boats was then a bare pole, for the fishermen specialized in the simplicity and paucity of gear. Some boats had no bowsprit at all.

Few used more than five pieces of standing rigging, two pair of shrouds set up with rope, and a forestay. Some had a stout piece of oak across the narrow foredecks, to give the fore strands spread, but they relied on the strength of their spars rather than rigging. "Make the wood take the weight!" said Doc, looking at his tough pine masts. He growled as Billy Sargent's big new Mamie passed us, with her slightly overlapping "racing jib" as he called it. It was a really very modest ancestress of the genoas of modern yachting.

OCTOBER TRAGEDY

"She drowned Johnny Gillam and his boy Howard the 16th of last October, a bitter day of wind and snow," he added.

It appeared that the new boat fancied favorite for the fishermen's annual New Year's regatta where Leckie's gave the prizes, and rigged accordingly, had been overpowered in a squall. It was not clear whether she was racing or not, but fishermen were always racing. Young Mac argued that she had too much or too little ballast, and they couldn't get it over to the right side fast enough when they were tacking. He was all for jibs, with their driving power, the bigger the better, with the enthusiasm of youth. The first fishboats had no jibs at all. That is why the foremast was still stepped in the eyes of each.

By this time we were a mile out and two miles up the shore in the direction of Hamilton, when Doc's eye picked up a six-inch patch of faded rag on the end of a stick, a quarter of a mile away,

"Take in that dam' jib," said he, "and then pick up that buoy."

PICKING UP

By the time we had the condemned triangle of canvas bundled below the fore deck the Bug was nosing up on the faded rag, and Mac hauled it and its cedar buoy on board, over the bow. Taking a turn around the foremast he lowered the foresail and mainsail without fuss, slacked off the single shroud on one side of the mainmast, unshackled the sheet, and swung the mailsail, gaff boom and all, completely around the mast, until he could lash the boomend to the foremast. This left the cockpit abaft the mainmast clear of everything but the tiller; and that was unshipped out of the rudderhead.

Then he carried the cedar buoy from the bow to the stern, and while the boat fell off into the trough, rolling and tossing gently until she rode stern-to, we all three began to haul in the buoy line over a wooden roller.

The net itself came harder, because it was bumpy with the cedar floats, which had kept it upright on the bottom, and with the lead sinkers, which anchored its lower edge down. Soon it came in slower still, for there was fish in it, here and there, not pocketed, but singly every few feet. It was a good few, Doc said, which in this case meant several hundred silvery herring, called ciscoes, questionably in honor of St. Francis. They were worth a cent apiece, $10 a thousand packed. He was less pleased at finding the net worse torn than anticipated and one or two fine Whitefish in it scaled and bloodsucked by "lampers," that is, lamprey eels. These little green and silver devils clung to their prey with their sucker discs even after their own heads were slashed off, "One good thing them black birds they call co'morants do," said Doc, "they feed their young-uns on lampers. But they ain't no co'morants up at this end of the lake."

Each ciscoe detached from the mesh which had caught his gills was tossed into an empty tray. Into another empty the net was slowly coiled as cleared. "Not that it's much good," grumbled Doc, "though with net twine the price it is we may have to make it do. I know it would be this way."

Instead of putting the torn net back in the water he bent on to the new one he had brought the old buoy and its anchor, and carefully paid it out over the roller, so that the sinker side would go down first. It was. straightened out as the Bug, still stern to wind, slowly dragged away from the spot where the anchor had been dropped. When we came to the end of the net the second anchor and buoy went over the stern too, and the invisible fence on the lake bottom was completed.

BEFORE GASOLINE

The wind had fallen to nothing now and Doc, anxious to get his fish on ice and his torn net on the reel, muttered the ancient formula about Armstrong's patent white ash breeze. He first threw overboard enough ballast to make up for the weight of the fish taken in. Three long, heavy narrow-bladed oars were detached from under the narrow decking of the Bug. A thwart, through which the mainmast stepped, ran right across her abaft the centreboard box. Near its ends were stout chocks for tholepins. Through each an oar was thrust. Doc put the third oar over the stern and began to scull and steer at the same time. Mac and I sat on the thwart with the mainmast between us, and pulled. It was a short tugging stroke, hard to get the knack of. "Keep your blade in the water till the last second," advised Mac, "and don't dip too deep. Mebbe it's easier for you to stand up and push." It was.

"Dang it!" grunted Doc, standing in the stern and swaying two handedly with his oar. "This is the darndest place on the lake for squalls and wind shifts! I mind the time the Erie Belle was dismasted offa Bronte with everything set. Five square sails she had on the foremast then. She was a big barque. And five men went overboard on her yards." He sucked a finger and held it aloft. "Wind'll be off the land in five minutes. 'Vast pulling, and get your mainsail swung back in place, Mac."

This was quickly done. The lake was still a silver mirror. The morning's lop had died out with the dying wind.

"Now give her the foresail," said Doc, "and I'll reef the main."

"HERE SHE COMES!"

He hauled out two reefs in the mainsail and tied them quickly with square knots, one part bighted for quick shaking out. Between us we had the sail reefed and set as soon as Mac had finished with the foresail. The sails had filled as they went up, and the Bug was easing gently through the still unrippled water, though the wind could hardly be felt.

"Here she comes, Mac," said Doc, A thin dark stripe of indigo blue was widening out from the land. Flecks appeared in it. Whitecaps. A downrush of invisible air was now scourging the water.

"Ease your foresheet, Mac, and don't you dare make it fast! You, what's-your-name, get those stones across the centreboard box quick, to port. Don't drop them. Swing 'em like eggs!"

The stone was easily handled, and a couple of hundredweight had been steadily shifted when the real "heft" of the wind hit us. Mac let his foresheet run, but was careful to keep the sail drawing. The Bug leaned till the lake water hissed along the lee strip of deck and a little splashed in on the fish. The weather side hove up so high that, from where I worked I could see nothing but the deck. "That's well with the stone!" called Doc, cheerily, "Get up on the weather side with Mac, and help him trim sheet! Never stay to leeward in a fishboat, for no man's say so. If she goes over, she goes over on top of YOU!"

BEATING HOME

It was exhilarating to get the fresh keen wind, full of the scent of ripe crops of strawberries and balm-of-gilead, and to see our rush through the splintered water. Other boats, which had finished their hauling or setting, were flashings about us like swifts, and the gulls, crying for fish guts, were shouting "To eat! to eat! to eat! Wanna eat! eat! eat!" as we all beat home together in short tacks. All jibless, all with reefed mainsails, with unsightly bundles of leach hanging festooned at the clews, for with no footropes it was impossible to pass a plait or otherwise tidy up the part of the sail overhanging the stern.

The Bug was not a clipper, and being small most others could outsail her, but Doc's judgment in using the oars and prompt appraisal of the wind put her well to weather at the start. Though others gained on her she reached smooth water under the lee of the little red-topped lighthouse first, and so entered the piers in the lead.

"What ship is that?" yelled Tom Joyce in derision from his Velveteena, our nearest competitor.

"Yah, what ship is that?" yelled Bob Joyce from English Lady, and Dick Joyce from the Gordon, and Jim Joyce from Genesta, and Bill Joyce from Volunteer. There were lots of Joyces fishing out of Bronte then. They were good professional yacht sailors, too.

"You can see it on my stern," retorted the skipper of the Bug with elaborate sarcasm, "unless I'm so far ahead of all of you yachtsmen that your binoculars won't carry so far."

The women on the wharf waiting to pack the fish, "caught on," and their shrill laughter mingled with the "To eat! To eat!" of the wheeling gulls.

Those were good days.

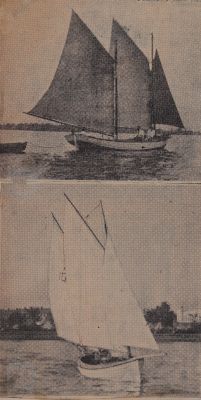

CaptionIn the foreground is a picture of the Duck Island fisheries of the Gauthier firm in Lake Huron, which fairly represents the Lake Ontario scene off Bronte any windy afternoon fifty years ago. The small "mack" to the right might be the BUG in this narrative, though she shows no bowsprit. Above her is the Bronte fish boat ITALCA, designed by Robert Hall of Hamilton seventy years ago. Fishermen did not like her, for she needed lots of ballast, but Stanley D. Baby of Toronto and his father, Capt. Jas. W. Baby, found her an excellent yacht, fast and weatherly. In the middle is a more recent Collingwood-built yacht of Mr. Baby's, the NAHMA, also a mackinaw and resembling such Bronte boats as had sharp sterns. Most of them were a square, like ITALCA's.

- Creator

- Snider, C. H. J.

- Media Type

- Newspaper

- Text

- Item Type

- Clippings

- Date of Publication

- 24 Jan 1948

- Subject(s)

- Language of Item

- English

- Geographic Coverage

-

-

Ontario, Canada

Latitude: 43.39011 Longitude: -79.71212 -

Ontario, Canada

Latitude: 45.708888 Longitude: -82.925833 -

Ontario, Canada

Latitude: 43.305865158053 Longitude: -79.46561359375

-

- Donor

- Richard Palmer

- Creative Commons licence

[more details]

[more details]- Copyright Statement

- Public domain: Copyright has expired according to the applicable Canadian or American laws. No restrictions on use.

- Contact

- Maritime History of the Great LakesEmail:walter@maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca

Website: